|

We have a very small herd of little black cows, Lowline Angus mostly and maybe a few with questionable parentage. They spend their summers out on our range pasture and nearly the moment they unload they become secretive little squirrels in around and underneath the sagebrush. They’re difficult to count. I’ve spent a fair amount of time with a spotting scope in our upstairs bedroom being the nosy neighbor attempting to find little black lumps with legs. Is that one there? Nope, just a rock.

So after having a possibly ill-conceived old-fashioned cattle drive to the fall pasture thwarted, we decided to ensnare the cows by offering morning feedings of a bale of hay. For two weeks, by 7:00 a.m., I threw a single bale of grass hay into our makeshift corral and yelled, “Come, Boss! Come, Boss! Cooome Booosss!” Now this is a phase my grandfather yelled to his cows, ostensibly to notify the lead (boss) cow that food is to be had. But yelling “Come, Boss!” at the top of your lungs sounds funny. Go ahead step outside, cup your hands around your mouth, and give it a try. I’ll wait here. Right? Hilarious. It comes out sounding like you are yelling “Come, Baaaaaas!” As if you’re Little Bo Peep looking for your sheep. It’s silly, but effective. After one week, I could yell and cows grazing down near the lake bottom would perk up their ears and come running, running at the sound of my voice. I felt mighty and powerful and Pavlovian. This is the low-stress farming version of propping a box on a stick and string to trap a bird. It never worked as a kid, but, boy howdy, I was happy to casually walkover to the gate and quietly swing it closed when I was *pretty sure* all the cows were inside the corral. Only one of our older girls, munching happily, looked up as I clicked the latch and I think she winked at me.

0 Comments

If cutting wheat is like a haircut for a field then baling straw is the barber whisking the hair off your shoulders and sweeping it into the dustpan. Once the straw and chaff roll, grind, and shoot out of the combine, the cut straw scatters across the ground. Fresh clippings wait to be picked up by metal tines and packed tightly into standard rectangles with plastic twine (orange AND blue, so flashy). This year I get to be the “barber” and am so excited at the prospect of running the baler (let’s be honest, happy to be out of the house without the kids) I may “misinterpret” dad when he tells me how many bales to make. But who cares? I am running the BALER! I skip figuratively to the tractor. The clunking and thunking of the packing arm rocks the tractor to and fro. I shove squishy orange ear plugs into my ears to drown out the noise of both the tractor and the baler. The dulled repetitive sounds of the engines are a strong contrast to the silent fluffy clouds slowly pushing northeast. My brother drives the combine in the distance and I periodically see dad work at getting one of the towers on the pivot irrigation fixed. At the end of a few hours of creating imaginary patterns in the field, the machine pooping out bales, I am dragging the baler behind me like a tired puppy. Bales have dropped off the machine at random intervals and now the field is littered. I ponder how I can make the pattern more regular next year and possibly create an aerial smiley face? But for this year, success! 163 bales. I report my general awesomeness to dad and he informs me that he had asked for about 100 bales. I am nothing if not an overachiever and possibly poor listener (the latter is certainly debatable and positive references would be appreciated). Luckily, straw bales are light, easy to buck, and I didn’t make too many to overfill the hay loft. As we picked up the bales and stacked them on the trailer to move them to the barn, I made myself extra useful by carrying two at once. I felt like this. I probably looked like this. Why didn’t anyone get a picture of that? (Insert gratuitous photo of adorable children below.) Wheat harvest is the best kind of harvest. Sorry, Corn. My bias knows no bounds on this subject.

There’s a magical moment when you step outside every year. It’s warm, sunny, maybe a little breezy, and you can smell it. Having given up the last of their moisture to the sky, the surrounding fields turn from green to gold. You know the smell in the kitchen as you mix bread dough? You turn on the oven, sift the flour, and begin to mix the ingredients. Just before you add the yeast that is what wheat harvest smells like. For a month every year you are wrapped in the warmth of dry wheat, light breeze, and pillowy clouds. It is all promise and possibility. Dad has a patch of irrigated ground in the pasture that he is cutting with an old John Deere 95H. Compared to modern combines the 95H is a postage stamp with a 22’ header. The windows have been removed, a fresh sheet of plywood dons the cab to provide shade, and chaff from the header blows up into your face as you captain the combine into the wheat. It’s hot. You’re covered in chaff and loamy dust and you’ll always discover a mystery spot of grease on your jeans. It is truly and genuinely fun. The best time of year. *Fire is bad in the summer in a semi-arid desert.

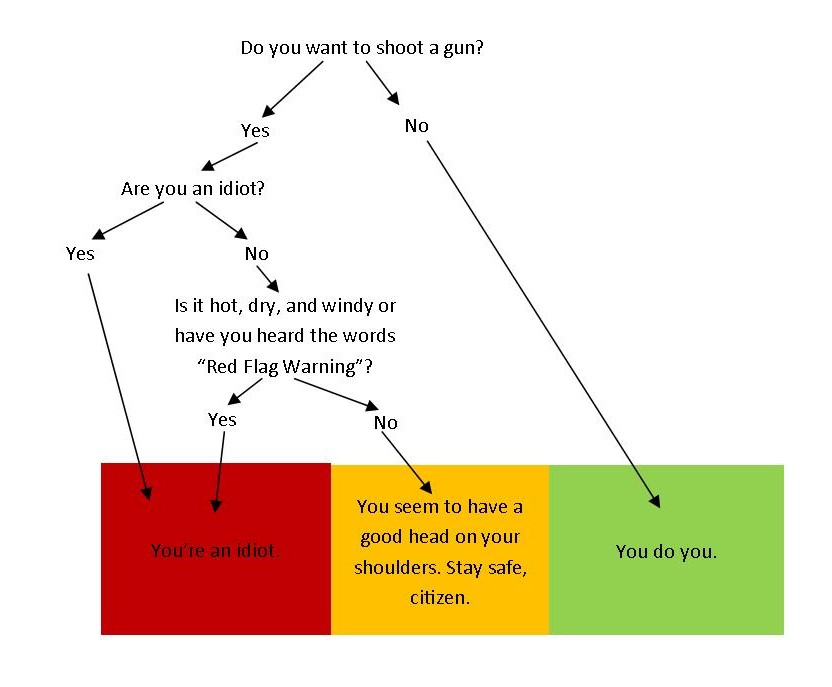

I’ve been involved in exactly two wheat fires in my life. Technically one, since the second fire was a flare-up of the first two days later. But we can talk about that another day. Fires start on a regular basis during harvest in our area. Given oxygen (e.g. my previous post) grassland and brush fires burn incredibly hot and fast. In the fields mechanical failures occur, bearings go out, or machines can just “get hot”. Farmers do everything they can to prepare for the unpredictable. Water trucks are equipped and readied right along with all of the combines, tractors, and trucks. A close eye is placed on hydraulic oil, zerks are greased, and filters are changed with regularity and care. For those that aren’t involved in harvest, fires can spark from the highway. Overheated cars or accidents spark fires. Even the trains can and have thrown sparks that take off. On windy hot days, I find myself sniffing the air for the smell of smoke seeking the horizon for ominous dark plumes. Smelling smoke on a breezy 90+ degree day sends a chill down my spine. These are all mechanical failures or accidents. That happens. I get that. But several local fires have begun recently because people were doing something stupid. More specifically people were shooting guns in dry grasslands on hot windy days and sparked fires because of ricochets against rocks. Yeah. That happens. So below, I have created a little flow chart to determine if it’s a good day to shoot a gun:  The wind is a near constant in our neck of the woods. And by woods, I mean scab rock, sagebrush, and dryland wheat fields. Our views are dynamic. You can see the sky for miles. But as a result we have little protection from gusting winds coming from the southwest. It blows and spits ferociously often leaving its moisture at the Pacific coast, blows through Oregon, and crosses the Columbia River to smack into us. Today it is warm, drying the plants and ground like the convection setting on your oven. When we moved home we put the windbreak to the southwest of the house. A drip-line was installed and the trees get periodic doses of fertilizer. About 100 little sticks dropped into the ground in four and a half rows have now grown to the size of... small bushes. We expect that in six years we may have a decent stand of wind-breaking, shade-producing trees. But until then I look out at the horizon and see the wind, having picked up a light layer of dust and a tumbleweed or two coming toward us. |

AuthorWhen passing out farm jobs, Morgane was awarded stall mucking, general nonsense, and internet miscellanea. She has since realized telling our story holds great and mystical powers. No takesies backsies. Archives

March 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed